Growing up, I do not recall feeling like I was a bad person. Don’t get me wrong, as a homeschooled teenager, I certainly was not overflowing with self-confidence or charisma. Aloof and awkward are more accurate. Everyone has areas where they feel incompetent, incapable, and in over their heads. I knew I was not perfect, and I am ever certain I fail at least as much as the next person.

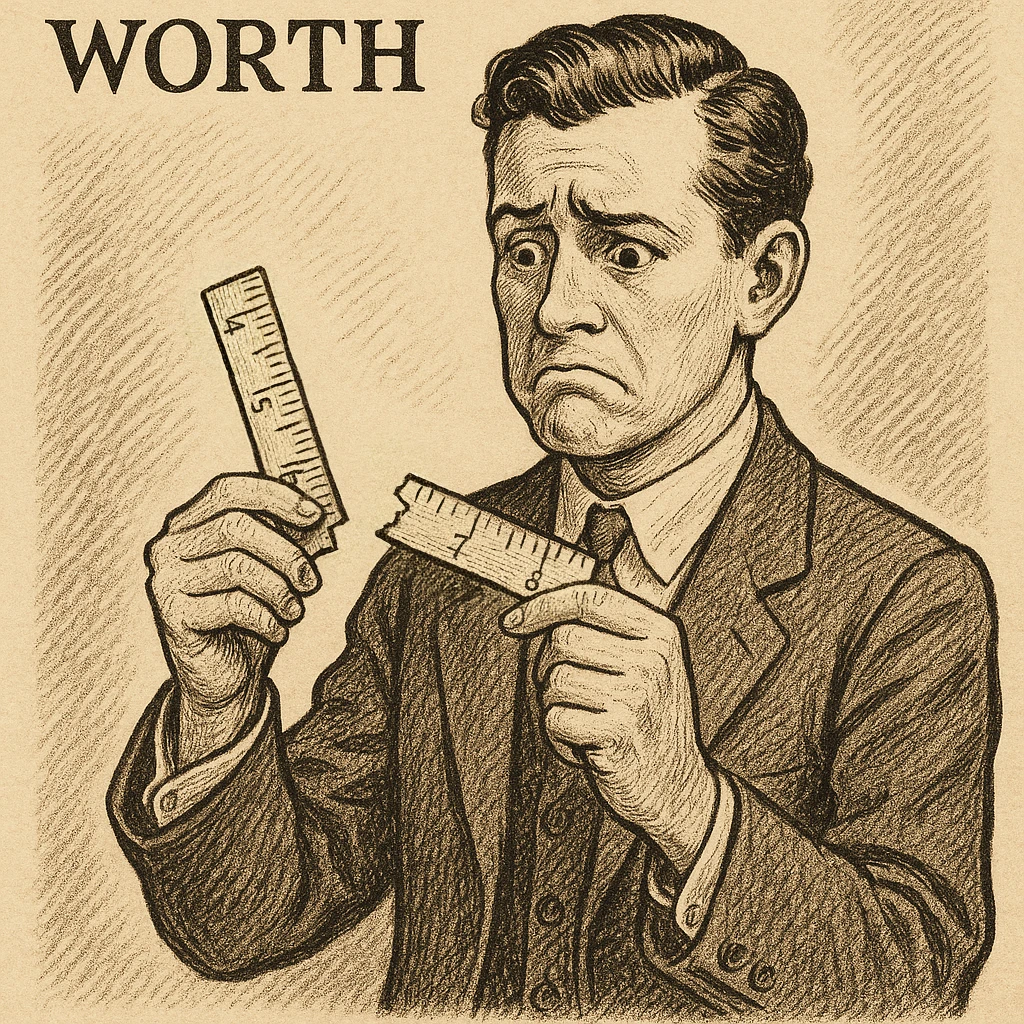

Who has not wondered if they were appreciated, likable, or even loved? Yet the question I am exploring here goes deeper: How do we view ourselves as human beings from the outset? How do we evaluate and measure our worth, and how does our worldview, biblical or otherwise, shape that perspective?

In recent years, Brené Brown has become well-known for clarifying the difference between guilt and shame. She summarizes it this way:

- Guilt = I did something bad.

- Shame = I AM bad, accompanied by feelings of worthlessness, undeservedness, self-loathing, etc.

This definition of shame frames “I am bad” as problematic and inherently tied to destructive emotions and beliefs. Is this correct?

Without saying these definitions are entirely wrong, what if they are incomplete? What if the problem lies in the angle of approach? When we define guilt and shame without a biblical framework, how might that absence distort our understanding?

Are These Definitions Biblically Accurate?

Scripture clearly teaches that humanity is sinful (Romans 3:23), and Jesus affirms the “natural man” must be born again (John 3:3; 1 Corinthians 2:14). Yet does this mean that those who are naturally sinful, inclined to evil, and born without inherited righteousness are worthless creatures, a waste of life, and undeserving of God’s love?

Adam and Eve felt both guilt and shame when they hid from God after disobeying His command (Genesis 3:7–10). Their shame was a legitimate signal that something had gone wrong; they were guilty. But understanding shame requires us to ask:

- Did God still love them? Yes

- Does a good parent love their child even when they choose wrong? Certainly.

- Why, then, did they feel shame? Because their sin led them to question their acceptability before God’s judgment.

What is the basis of a child’s worth to a parent? Is it their performance, or their inherent relationship as a son or daughter? The same holds true for parents who adopt a child. In both cases, the child’s worth is measured by the love of the one who claims them, not by their perfection.

Until then, Adam and Eve’s worth as God’s children had been grounded in love and trust. Yet in the wake of their disobedience after introducing a break in that relationship, they began to base their confidence and value on their performance in relation to God’s command. As they measured their failure against God’s expectations, they recognized their deficit, and shame took hold. They hid, tried to fix what they could, and shifted blame when they could not. Their confidence and shame were now securely fastened to performance, and survival of the fittest had begun!

If worth is based on performance, and performance is poor, there is nothing left to build confidence on until we believe we are doing more good than bad, or deceive ourselves into thinking so. Every sense of worth becomes tied to the fragile balance of achievement and failure.

As a parent, I do not require my four-year-old to fix what she breaks before I extend love and forgiveness. But in life, we often act as though God requires perfect performance before He can accept us again. Feelings of shame lead us to measure our performance, or at least deceive ourselves into feeling better by finding someone worse to compare with.

“If you see your sinfulness, do not wait to make yourself better. How many there are who think they are not good enough to come to Christ. Do you expect to become better through your own efforts? … We can do nothing of ourselves. We must come to Christ just as we are.” SC 31.1, cf. Jeremiah 13:23

As With Adam and Eve, So With Us

When we feel bad because of our sin, we face an opportunity: Will we receive God’s love, forgiveness, and healing, which are given apart from our ability to measure up? Righteousness comes by faith, not through penance or works (Romans 3:28). A healthy relationship does not thrive when we intentionally keep wounding and sabotaging it, but victory flows from love, not from earning that love.

Defining Guilt and Shame Biblically

In undergrad, I learned a better distinction that has stuck with me:

- Guilt: A message from God that humbles us and encourages repentance and faith rather than fixation on how bad we feel.

- Shame: A distorted message that discourages faith, promotes unbelief, hiding of wrong, disassociation, or self-atonement, ultimately leaving a broken relationship with God unresolved.

Jesus taught that our actions reveal our nature. Bad trees produce bad fruit (Matthew 7:17–18). The Bible declares both the murderer and the liar as condemned without Christ (Revelation 21:8). Guilt arises from our identity and what that says about who we are, but this is an opportunity for faith, not self-flagellation in shame.

Brené Brown’s framework sees “I am bad” as inherently harmful and problematic, but biblically, acknowledging “I am bad” can be liberating if it drives us to God rather than away from Him. This is not shame; it is guilt rightly understood, and it prompts humility and faith. Denying the disease blinds us to the cure.

Consider This

- The idea that we are bad because we do bad things is common to legalism and has it twisted.

- It makes us believe that if we just tried a little harder, we could finally deserve acceptance and love. This belief perpetuates shame.

- The gospel reveals that although the tree is bad, God offers to graft us into Himself (John 15:1–5; Romans 11:17), transforming both root and fruit.

This is incredibly freeing because we no longer have to measure worth by effort. Right doing thrives when rooted in God’s love rather than in the fear of not being enough. Success becomes possible when enabled by God’s power, which we otherwise lack.

The Foundation for Freedom

- Believing we are born sinless or morally neutral shifts the focus onto our performance, which will always seem imperfect for a sense of worth.

- The Laodicean message reminds us of our true condition precisely so we will seek solutions outside ourselves (Revelation 3:17–18).

- Recognizing the disease of our sinfulness directs us to the cure in Christ.

In the end, a Biblical, realistic, guilt-calibrated view of our innate sinfulness allows Jesus to address our sin at the root rather than just the fruit. Instead of bringing about license to sin, it orients us to the only solution so we can stop making excuses. It shifts the focus from the insecurity of our inability and lack of righteousness to His ability, righteousness, and love.

Our brokenness is not the despairing end of our story. It is the invitation to exchange our poverty for His riches, our nakedness for His robe of righteousness, and our blindness for His healing sight. It is, ultimately, the opportunity to allow God to show us that we are valued and loved, no matter what we’ve done or how we feel.