By Eric Louw, M.Div. & Esther Louw

If you’re a millennial or older, you probably grew up with the KJV, memorized Bible verses in it, and maybe even came to love the eloquence that makes it so distinct. In some ways, I am no exception. At the same time, I also had and read other translations, and sooner or later, I became aware that there were differences between them. How could this be? Which one is true? And is one more reliable than the rest? No sooner is the question asked, and one discovers that this is a cause of a great divide among many. What follows is an outline of seven considerations to inform you about critical areas of discussion often overlooked in version debates.

Consideration 1: Dead Words and False Friends

Most English speakers today do not correctly understand the KJV. There are two reasons for this:

- Dead words: Words that are no longer in use.

- False Friends: Words that are still recognizable today but have different definitions, misleading people to believe that they know what is meant when they mean something else.1

A long time ago, there was a cartoon called The Flinstones with stone-age characters named Fred, Wilma, Barney Rubble, etc. The intro song lyrics said, “We’ll have a gay ol time!” Does that mean they were all gay in the sense it is defined and most commonly used today? No. Different times, different definitions. You’re liable to confuse the meaning if you aren’t aware of both.

82% of the world’s population does not speak English. Only 5% can speak English natively.2 This means a “KJV-only” position is unfeasible for most people. Subtract those who do not understand Elizabethan English, and probably only 1% of them can still understand the KJV.

Do you have what it takes to be part of that 1%? Discover how you score in this quick, anonymous, 2-minute KJV Comprehension Challenge (or see the results here).

The KJV was originally written so “plow boys” could understand, yet today, this is no longer true. What the KJV beautifully did in its day to make the Bible accessible to all is no less needed today.

So why not just translate Bibles from the KJV into other languages?

As anyone who has ever played a game of telephone will know, translating Bibles from an English KJV to other languages would introduce a much larger margin for error. It adds an additional layer of errors on top of those already present. This would be far less reliable when compared with translating directly from Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek into a target language.3

Consideration 2: Growth in Understanding of Biblical Hebrew and Greek

Biblical Hebrew, Aramaic, and Koine Greek are not spoken languages anymore. Many words translated into English only occurred once or twice in the manuscript base referenced for the translation of the KJV. Over time since 1611, subsequent discoveries and archaeological findings of additional manuscripts have provided us with a more precise understanding of what many words mean because we have more examples of how they were used in Biblical and contemporaneous contexts. This means that a student reading Koine Greek or Biblical Hebrew today can understand and translate the text with a better grasp of how many of the words should be translated. There have also been advances in our understanding of grammatical constructions common to Hebrew and Greek, which also play a significant role in understanding meaning and emphasis in translation.

Consideration 3: Language Translation is Complex

Most people don’t have a working knowledge of biblical languages and cannot read or translate them. This is important because translating Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek is not a matter of translating each word in a 1 to 1 equivalence. This can be surprising for first-time Bible language learners.

Most sentences in the Bible require that words be supplied or omitted to be readable with correct English syntax. This doesn’t mean that translations are unreliable, however.

The Biblical languages embed a lot more grammatical information into nouns and verbs than English does:

Nouns embed:

- Person (1st, 2nd, 3rd),

- Grammatical gender (Masculine, Feminine, and Neuter),

- Number (singular, plural),

- Case (nominative, genitive, dative, accusative, and vocative, which indicate function in a sentence).

Verbs embed:

- Tense (present, past, future, perfect, and more),

- Voice (active, middle, passive),

- Mood (the manner of a verbal action in relation to reality),

- Aspect (perfective, imperfective, and stative – viewpoints in reference to a verb’s action).

This detailed information is all embedded with word inflection. This is similar to how we might change the word “run” to “ran” to indicate past tense, though we typically use additional words to account for other grammatical elements. Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek can embed much more into each word.

“Illegitimate Totality Transfer”4

Besides just sounding intriguing, this fallacy occurs in the following way. Suppose you have a particular word in a specific context, and you decide to look the word up in a concordance or lexicon. You will probably discover many other usages of that word from different contexts there. A good lexicon will hopefully give you the total semantic range of the word, along with a breakdown of these different types of usages. Now, if you simply say, “Aha! This word here could be any of those meanings!” and plug it in, that is illegitimate if you do not first consider the context in which it is used.

A well-known individual once referenced a concordance and observed that the pronoun הוּא in Exodus 20:8 can be translated in various ways, including “he, she, or it.” Capitalizing on this discovery, he decided that the word “it” in “Remember the sabbath day, to keep it holy” could, therefore, be substituted with “Remember the Sabbath day, keeping yourself holy.” Had he known that this Hebrew word in Exodus 20:8 was a third-person, singular pronoun that must agree contextually with its antecedent, he would have known that plugging in the word “yourself,” which is a second-person, plural pronoun, was utterly incompatible and contradicted how the Biblical writer intentionally inflected the pronoun.

When engaged in Bible study, be careful not to read meanings into verses without letting the context and grammar indicate the meaning.

Consideration 4: Translations are not Infallible

Fun facts:

- The 1611 edition had two editions known as the “He” and “She” editions, based on how Ruth 3:15 was rendered as either “He” Boaz or “She” Ruth entering the city.

- There were revisions in 1629, 1638, 1729, 1762, and finally, 1769, the Oxford Standard edition used today. These differ in thousands of places from the original 1611.

Because of the complexities involved in translation with manuscripts that may not always correspond perfectly to the lost autographs, it is helpful to recognize that no translation is infallible. Certainly, the KJV, on average, should be no less fallible than other formal translations. Translators make thousands of choices when translating. Most Christians do not believe that God inspired translators as he did Bible authors. At the same time, this does not mean that God cannot guide translators, just as he guides anyone seeking to read and understand His word. Still, this is no guarantee of infallibility, or all Christians would believe similarly, and denominations need not exist.5

If you believe it is essential to read the very least error-prone version, there are two options:

- Learn the original languages and read them directly.

- Be in favor of versions that have been translated with a more precise understanding of the languages.

Consideration 5: Translator Bias and Errors Do Not Defeat Doctrine

If one assumes modern translations occasionally mistranslate a text due to translator bias that the translation committees did not catch, there are two things to consider:

- This applies to all translations. The Authorized Version (KJV’s) translation process was not immune to bias.

- The precision offered by 400+ additional years of discovery and study in biblical languages means that modern translation is far more precise.

For those concerned that verses may have been systematically mistranslated deliberately, this is less consequential than one may assume. Even if they were, the Bible is of such a broad and deep character that no translator or group of translators can easily remove any foundational doctrines because the truth is not based on only one or two proof texts. Most doctrines are thoroughly grounded across many texts and narratives throughout scripture. Even the New World Translation, translated by the Jehovah’s Witnesses, can still be used to prove the divinity of Jesus despite their efforts to obfuscate it. If a Bible student studies broadly as good Bible students should, they will see how doctrine harmonizes throughout the canon.

Rather than being a significant problem, exceptional cases of apparent contradictions can prompt Bible students to investigate further to determine if the issue is based on 1. Personal presuppositions, 2. a lack of contextual understanding, or 3. the way a verse was translated. These are opportunities for growth for Bible Bereans like those in Acts 17:10–11.

Consideration 6: Not all Bibles are Translated using the same Approach.

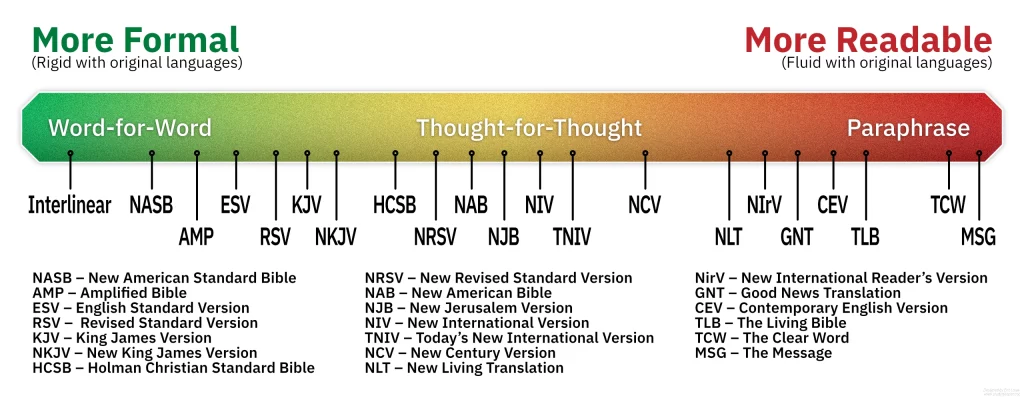

There are at least three different approaches to translating from the original languages:

- A literal, rigid, nearly word-for-word approach to translating the original languages. These represent each word as accurately as possible, even if this makes the translated sentences more complicated (Interlinears, NASB, AMP, ESV, RSV, KJV, NKJV).

- A mostly literal, thought-for-thought approach that still avoids paraphrasing (NIV, NAB, TNIV).

- A fluid idea-for-idea approach that aims for maximum readability by paraphrasing. These are the most liable to introduce translator bias (NLT, TCW, The Message).

Overly rigid translations can see a loss in accuracy when directly translating foreign idioms. On the other hand, how words are used in combination with verbs do not always have equivalent meanings. So while NASB might seem the best, it could actually be confusing or even misleading in some cases.6 While many of these issues may be overcome by thought-for-thought approaches, this also introduces a different margin for error if the thought is misunderstood or colored by a preexisting bias. So, in the end, something leaning towards a rigid approach, while not extremely formal, can be best (see the graph below). It is ideal to compare 2 to 3 different translations when studying the Bible if you do not know the original languages, as this can help account for such issues.

Here’s a visual overview of some common translations associated with each approach:

NKJV and ESV are mostly literal while still relatively easy to read, whereas NASB can be more rigid and helpful for comparison.

Consideration 7: Manuscript Streams and Availability

- Autographs. The original documents of Scripture no longer exist and have been lost to history. We only have manuscript copies (5,000+ New Testament, 600+ Old Testament). The Oldest NT Manuscript is from ~200 AD, and no two manuscripts agree 100%.

- Erasmus (A Dutch Catholic) only used maybe 10–12 out of 3,000 in the Byzantine (Majority Text) for his Greek New Testament. Most dated from the 12th and 13th centuries, so they were not particularly early. He published several versions beginning in 1516. His Greek New Testament came to be known as the Textus Receptus (Received Text). KJV used the 1522 edition, which was his third edition.

- Missing Sections Supplied with the Vulgate. The translators of the KJV had Erasmus’ manuscript available to them and several other later editions of the Greek New Testament that were based on a similar set of manuscripts (one by Beza and one by Stephanus). All three scholarly editions, including Erasmus’, relied heavily on the Catholic Latin Vulgate to help piece together sections where the Greek manuscripts were damaged and missing content. Although these three editions were based on almost the same Greek manuscripts, KJV Translators used all three. Despite this, even when the Greek manuscripts were fully present, sometimes the KJV translators preferred the Latin text anyway. One example is Luke 2:22, in which the KJV translators followed the (incorrect) Vulgate reading. Frederick Scrivener was a nineteenth-century scholar who carefully sifted through manuscripts to determine the Greek readings behind each of the verses in the KJV. He astutely observed: “In some places the Authorized Version [i.e., the KJV] corresponds but loosely with any form of the Greek original, while it exactly follows the Latin Vulgate.”7

- Text Types: These are groups of manuscripts/texts that appear to have a common ancestor based on similarities in how they read as well as similarities in how they differ. Critics sometimes oversimplify a complex issue by making it about differentiating between three manuscript streams, when there are five:

- Alexandrian – Taken to be the best by most scholars.

- Egyptian – Similar to Alexandrian, but distinct.

- Western – A smaller group of manuscripts. Sometimes, they have odd readings.

- Caesarean – Somewhere between Alexandrian and Byzantine

- Byzantine – Taken to be the latest text from the Byzantine Empire. A lot of these were focused in Turkey. It is known as the “Majority Text” because it represents the most extant manuscript copies.

It is important to note that with few exceptions, most of the differences are minor, amounting to individual word or word order variations, and pose little risk at the level of doctrine as discussed in Consideration 5. That being said, variants can sometimes affect how individual verses are interpreted in their immediate context.

Some hold the Byzantine text type to be the best based on two theological ideas:

- God protects His word from corruption. This idea is valid in a general, broad sense but not typically focused on addressing details in manuscript copies, which can vary even among individual Byzantine manuscripts.

- The Byzantine text has the correct doctrines, orthodox doctrines. How do you know these are correct? Because they’re there. Hello, circular reasoning.

In most cases, Bible Version debates center around text types. Yet, when one considers everything else discussed so far, the other factors have a far more significant impact on theology and understanding for more people in day-to-day life than text types.

Still concerned about this? Select a Bible translation that lists significant differences in the footnotes. Good Bible translations allow the individual to consider variant readings personally. Most modern translations list substantial variations in a footnote between all except the Byzantine text type because many believe the Byzantine text type is a more recent smoothing of earlier streams. Nevertheless, the NKJV lists all of them.

Summary:

- Elizabethan English contains many words that have shifted meaning beyond even remote similarity today. The majority of readers today do not understand many of them. Many that seem recognizable often mean something else. Furthermore, most people on Earth do not speak English, and those who understand Elizabethan English are probably fewer than 1%.

- Our understanding of Biblical languages is far more precise today than when the KJV was produced. This significantly adds to the precision possible in the translation process.

- The translation process is complex. Noun and verb inflection and consistent grammatical rules mean that there has always been far more decision-making involved in Bible translation than most realize. This is why there were thousands of changes between the various KJV releases.

- The potential for bias during translation was just as present in 1611 as today. Translators are not held to be infallible. The best way to demonstrate care for accuracy is to learn Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek so that you can read them directly.

- Translator bias and occasional translation errors are not enough to compromise doctrine as long as you study broadly and don’t base your faith on a single text.

- The best version is the one that is read with maximal understanding. For most people, point #1 alone would necessitate moving from KJV to something they can understand accurately. For accuracy, pick a more rigid translation of the original languages.

- Manuscript stream discussions and concerns aren’t an issue if you use a translation like NKJV, which indicates variants across text types. Many modern versions will indicate most variations in a footnote.

In the end, the best Bible version is the one that is readable and, as a result, read regularly rather than left on a shelf to gather dust because it is too hard to understand. “Your conversion is more important than your version.”8

I prefer ESV, NASB, and NKJV, but also take a look at NLT from time to time just to get a feel for how the same text might sound in the smoothest modern English, while recognizing that it is a paraphrase.

Do you want to get into studying your Bible more meaningfully? Check out: Surrendering Our Ideas on YouTube or StudyDeeper.org

- “How Many People Speak English,” WordsRated, https://wordsrated.com/how-many-people-speak-english/ ↩︎

- This was demonstrated in the 2019 Authorized documentary by FaithLife. ↩︎

- Telephone is a children’s game where a message is passed on by whispering it from person to person in a chain. At the end, the original and final messages are compared to see how much the message has changed. ↩︎

- James Barr coined this fallacy in The Semantics of Biblical Language, 1961 ↩︎

- When the New Testament makes quotations from the Old Testament, these quotations and allusions are often word-for-word quotations from the Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Old Testament that was already in use during Christ’s incarnation. A great example of this is Revelation 14:7, which perfectly quotes the Septuagint version of the fourth commandment, demonstrating that the Sabbath is at the center of the First Angel’s Message. ↩︎

- Thanks to David Hamstra for pointing this out. ↩︎

- Frederick Henry Ambrose Scrivener, The New Testament in the Original Greek, According to the Text Followed in the Authorized Version (Cambridge University Press, 1894) ix ↩︎

- Dan Serns, 2024 ↩︎